A famous bridge and an infamous battle

We arrived in Mostar, one of the main cities in Bosnia and Hertznegovia, expecting to see a famous example of Ottoman architecture. Other travelers had told us the Stari Most (“Old Bridge”) was beautiful and worth seeing, although there wasn’t much else worthwhile in town. But for me the bridge ended up taking a backseat to the eye-opening devastation and stories from the Bosnian war.

We stayed at a great hostel, Nina’s Hostel, run by a welcoming grandmother (Jadranka) who made it clear how thankful she was to have tourists return to Bosnia. She was Orthodox Christian, married to a Muslim man, and her family was the perfect guide to, and example of, the ethno-religious tensions and ties in Bosnia following the collapse of Yugoslavia. Jadranka picked us up from the bus station in her personal car, cooked us breakfast and dinner without prompting or any indication it was included, and arranged for her sons to give us a personal walking tour of the town.

Her sons had remained in Mostar throughout the war and had some gut-wrenching stories to tell. While the full story is easily found elsewhere, it was shocking to see the huge number of buildings still in ruin or still containing bullet holes from the war nearly two decades earlier. In short, Mostar lies in a valley between two hills, and the hills during the war were occupied by the Catholic Croatians and the Orthodox Serbs. Both of those parties agreed that they wanted the Muslim Bosnians to have as little land as possible. Stuck between the hills, it created monstrous conditions for the town, whose residents were rarely out of range of snipers.

Most striking to me was that the town was about half Catholic, half Muslim, both before and after the war. During the war the two sides fought each other bitterly, residents taking revenge on fellow residents. Our guide told us that everyone knew of people they had known before the war doing terrible things to former friends. As an interfaith family, our hosts were right in the middle of it. But with the war’s conclusion, without any way to divide the city, both groups remain residents of the same city. And while the town claims that the war’s rifts have healed, from an outsider’s perspective the divisions are still simmering just below the surface. There are still two city halls (one on the Muslim side; one on the Catholic), two fire departments, and two Police headquarters. Even in a reconstructed school that teaches both Catholic and Muslims students, supposedly a symbol of the city’s renewal, the Muslim and Catholic students are taught in separate classrooms from separate textbooks. Sadly, it seems clear that a final resolution has not been reached.

This street was the front line during the war. Most of the building have been rebuilt, but all used to look like the destroyed one.

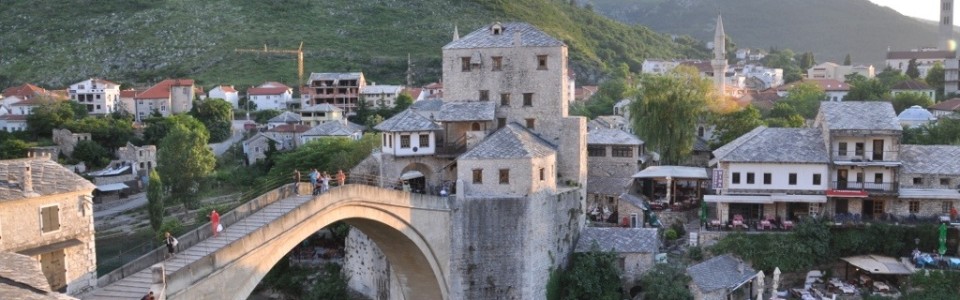

The bridge was as pretty as advertised. It was destroyed during the war but reconstructed in the same style a few years later by UN funds. While touristy, it was fun and interesting to see the old streets and shops from what had been an important Ottoman trading route.

The highlight of the bridge was the jumpers, who (once a suitable amount of money has been raise from tourists) jump from the bridge into the shallow and fast-moving water below. They prohibit others from jumping, both to keep the bridge jumpers a small fraternity, and also for safety – a few months before we arrived a European tourist who didn’t heed the warnings was killed jumping from the bridge.